While artists have long drawn inspiration from literature, a new symbiotic relationship has emerged in recent decades between theatrical cinema and the visual arts. Since the inception of the medium, movies have interacted with the creative arts across artistic movements and country lines, such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis referencing The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Stanley Kubrik’s A Clockwork Orange alluding to Prisoners Exercising by Vincent Van Gogh, and Lars von Trier’s Melancholia interacting with Ophelia by John Everett Millais. Given the relative nascency of the motion picture, this relationship has existed as a more lopsided affair, with movies often drawing from historical works, and not the other way around.

As a film fan, I became interested in the reversal of this interrelation, curious of how our member artists’s work might contain droplets of influence from the silver screen, and what each artist’s favorite film might say about their work, themselves, or simply their current interests.

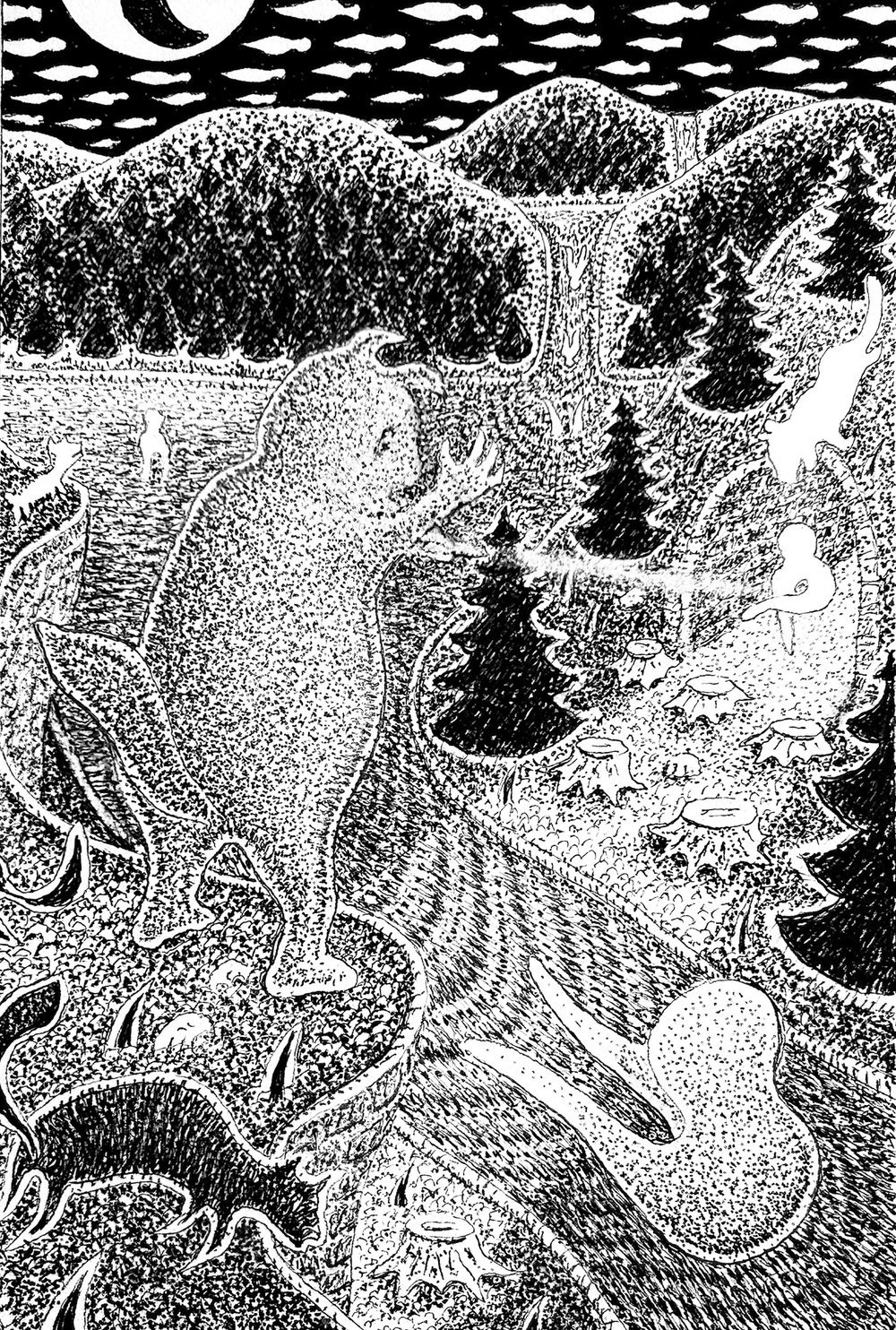

WAYNE PAIGE

Paige’s favorite film, Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), portends a futuristic dystopian society teeming with surrealistic encounters of its main character, played by Jonathan Pryce. Onscreen as pencil-pusher Sam Lowry, Pryce persistently escapes his monotonous life through a recurring daydream of himself as a virtuous hero saving a beautiful damsel. Easily renamed Whimsical 1984, the movie depicts a bureaucratic, totalitarian futuristic society while maintaining a light zaniness to it, leading Pryor into consistently bizarre circumstances within the confines of his society. Like the content of the film, Paige’s work “taps into subjects that include conflict, dreams, and humor.” Similarly, he works “strictly with [his] imagination,” creating landscapes that “serve as settings for a variety of unforeseen events.” To read this blurb further, please submit form 27B-6, as I'm a bit of a stickler for paperwork.

Brazil (1985) still from FILMGRAB

Brazil (1985) still from FILMGRAB

Another End to Another Tunnel by Wayne Paige, Archival ink on paper, 2023

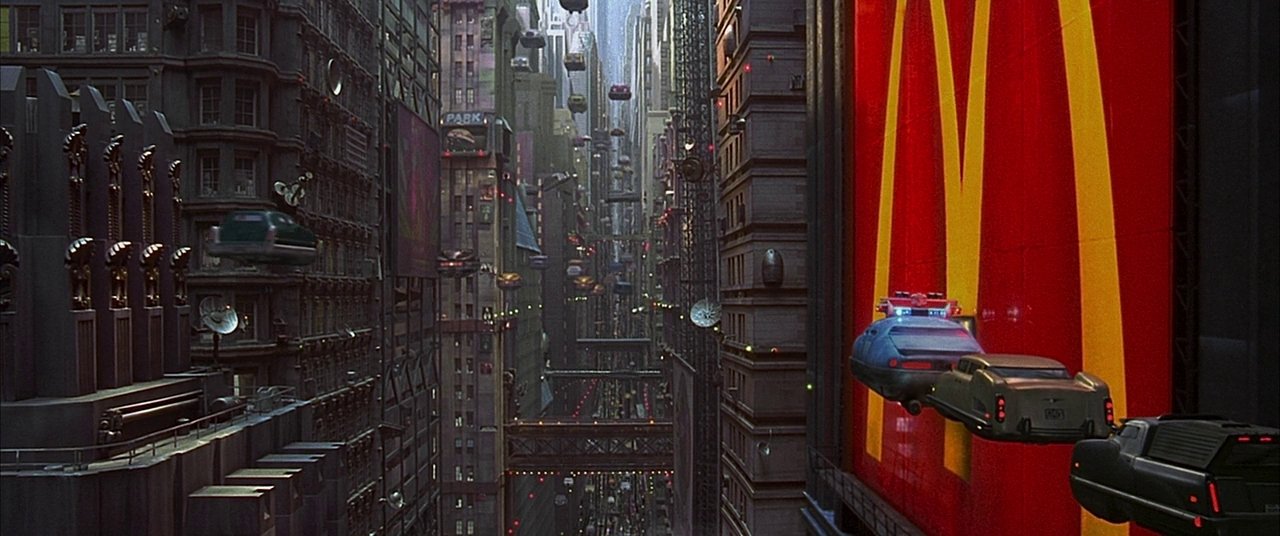

ELIZABETH CURREN

Sticking with sci-fi, Curren’s favorite movie, Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element (1997), depicts a twenty-third century U.S. as a taxi driver, Bruce Willis, becomes embroiled in a plot regarding the future of humanity after a young woman, Milla Jovovich, falls into the back of his cab. A visual cheeseburger, the film maintains a combination of old-world style elements mixed with futuristic touches, such as flying yellow taxi cabs and antique Chinese ceramic teaware being used on spaceships. Adding to this curated and kooky world building, the costumes were done by famed designer Jean Paul Gualtier, who created over 1,000 ostentatious and intricately detailed costumes for the film, going so far as to hone in on the outfits of extras. While not specifically influencing her art, Curren has “always been fascinated by space,” as well as the “intersection of art and science,” which is certainly present in the film.

The Fifth Element (1997) still from FILMGRAB

The Fifth Element (1997) still from FILMGRAB

Super Moon by Elizabeth Curren, Watercolor, gouache paint, crayons, wax crayons, on overbeaten flax, 2018

JO LEVINE

Although reluctant to pick an all-time favorite, Levine noted that her current taste lies with Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2023). Margot Robbie, acting as the titular character, lives in the paradise of Barbie Land with Ryan Gosling as Ken, before the two embark on a journey of self-discovery, learning about the joys and pitfalls of living in the real world. Levine loved the “deliberately unrealistic sets in Barbie Land” and the “fabulous outfits the Barbies wore.” Countering Levine’s artistic focus on details that “pass unseen by a world too busy to notice,” one can’t help but notice each and every bubbly feature in this film. While the artist notes that the film has no relationship to her photography portfolio, it might reflect her current state of mind, as she “want[s] to live in the sunny, pink, feminist paradise of Barbie Land, where life is always a beach!”

Barbie (2023) still from FILMGRAB

Barbie (2023) still from FILMGRAB

Female Totem by Jo Levine, Archivally printed photograph

HALLEY STUBIS

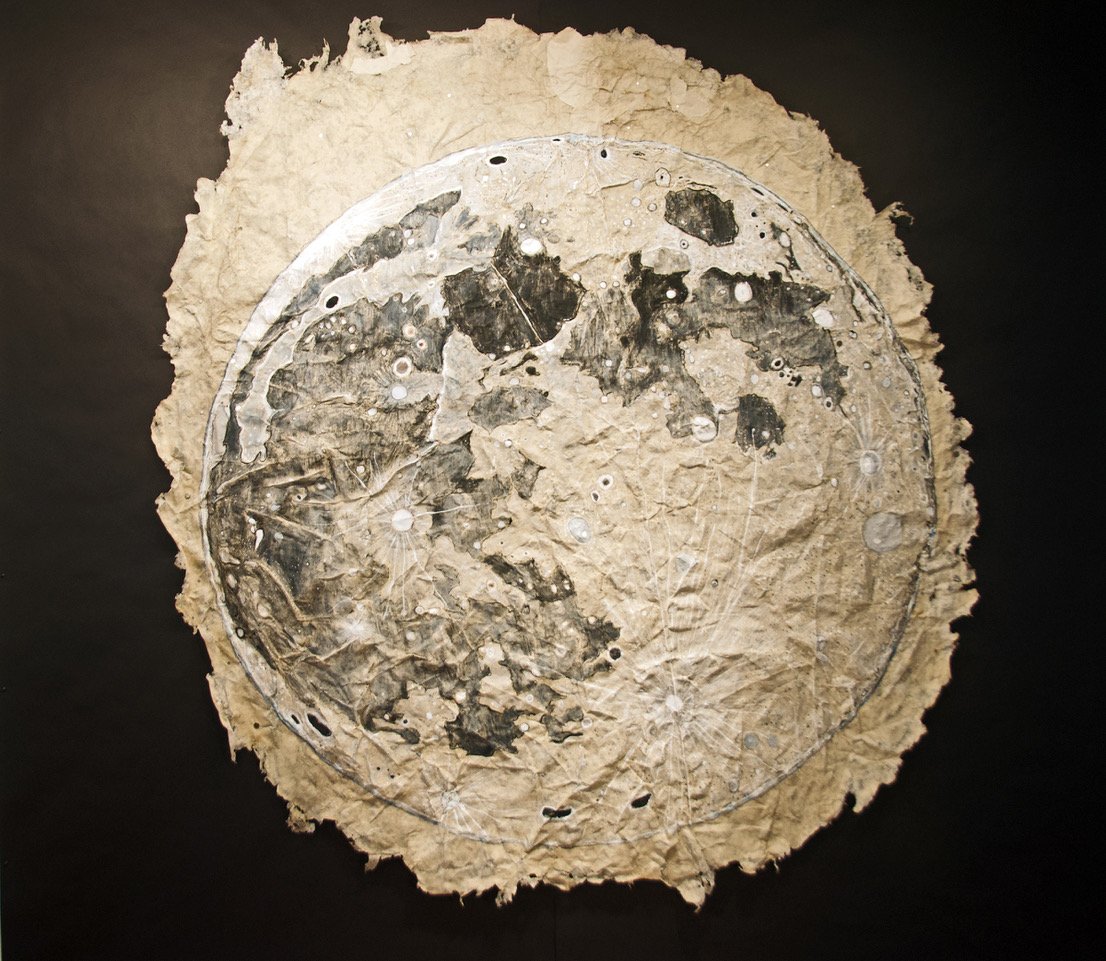

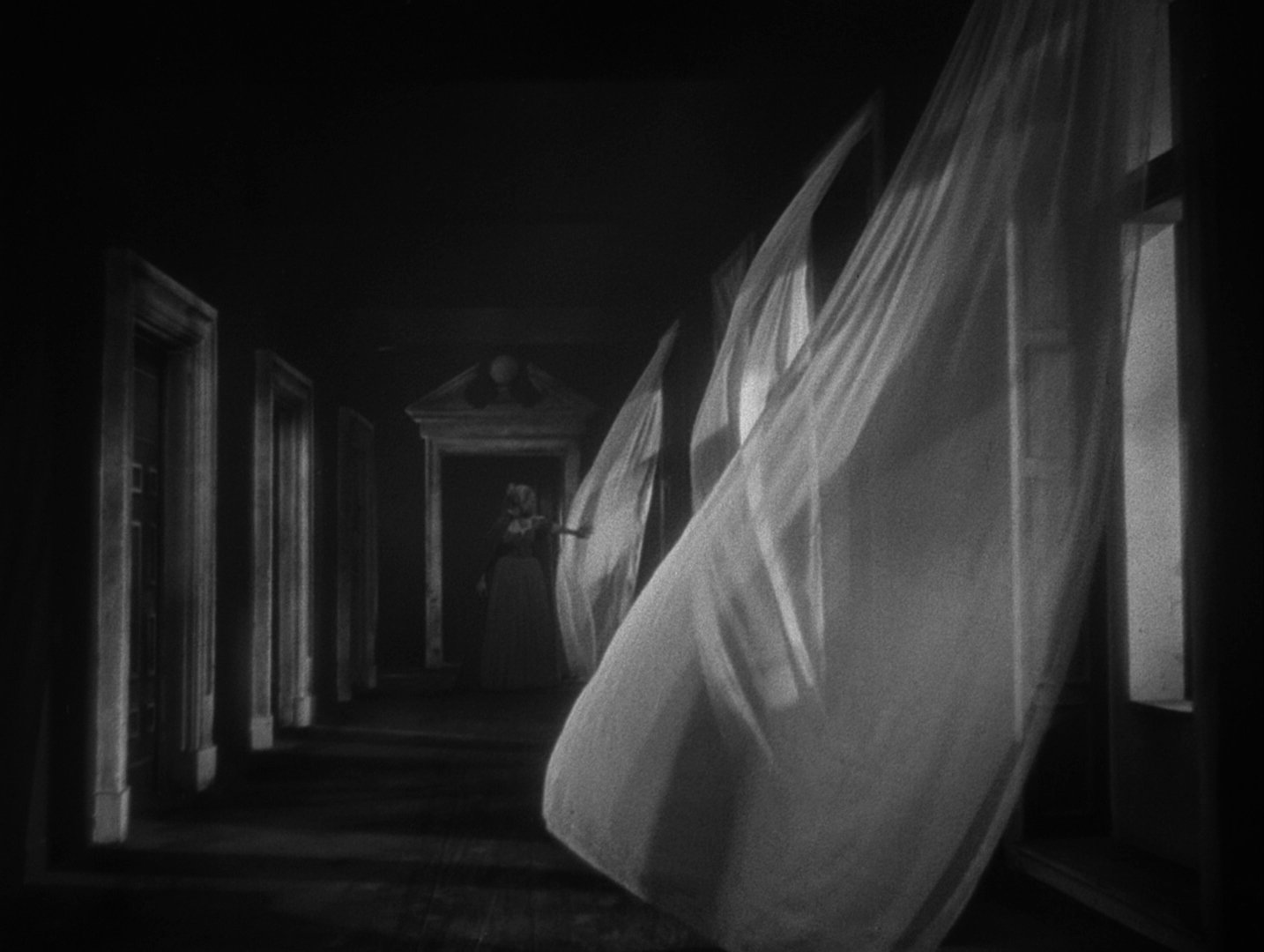

For our beloved Director Halley Stubis’s pick, we take a trip back in time to 1946 to take a look at Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast). While sharing a storyline with the familiar Disney classic, the film deviates almost entirely in its representation of the classic story. While I could convey Stubis’s response, let’s hear it straight from the Director, as illustrated below:

“I adore this movie because of its history and fantastical special effects-- a huge deal at the time, as they of course didn't have special effects technology back then. Everything was done using "practical effects", meaning they were done by hand. This movie, a well-beloved and well-known fairytale, has many fascinating moments where the ambiance is expertly set through Cocteau's creative abilities. I grew up in a household of artists, including dancers, visual artists, and writers so I have been fortunate to have grown up learning about the arts (My grandfather Tālivaldis Stubis designed movie posters and was a prolific artist, with the poster for Funny Girl being a well-known example). Seeing this movie as a child really had an impact on me. Two scenes stick out to me in particular: the first is when la Bête (the Beast) carries the fainted Belle through a doorway in his magic castle. At this point in the movie, she is a newcomer to the castle and to the Beast. She is wearing a basic commoner's dress, old and tattered. As she is shown being carried through the doorway, her dress transforms into one of glittering fabrics and extravagance. The second scene, when she first enters the castle and discovers that it is alive, shows many arms coming out of the walls along the hallway. They are all perfectly spaced and poised, moving in unison and holding up torches to light Belle's way through the castle. Both of these scenes have striking visuals that I feel modern movies are not able to achieve due to the handmade quality of the effects. They are hauntingly beautiful, like Dali dreamscapes that are just lifelike enough to truly frighten and enchant you. The beauty and care put into this movie take my breath away.

I definitely see resemblances of La Belle et la Bête to my current artwork. I love themes of storytelling (especially fairytale elements), dynamic portraiture and ways of representing the human body, as well as the idealized tinged with the reality of the grim. I tend to use motifs of natural elements in my work (flowers, thorns, water, etc.), and find myself drawn to the strangeness of the human condition. I can absolutely see how my artistic style today might have been influenced by Cocteau.”

La Belle et la Bête (1946) still from FILMGRAB

La Belle et la Bête (1946) still from FILMGRAB

Moonlit by Halley Sun Stubis, Digital painting, 2022

John Swords

It’s never easy to pick a favorite, but I feel wholeheartedly steadfast in my promotion of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972). Psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis) is sent to a space station that orbits the titular planet to investigate the death of a crewmember as well as assess the mental afflictions of the remaining two cosmonauts. Unbeknownst to him, the liquid on the surface of Solaris functions as a sentient being, bringing out repressed memories and obsessions of those who encircle it, resurfacing a representation of Kelvin’s dead wife Hari.

What makes this film special to me is that although it is set in space and thus undoubtedly a sci-fi film, it’s a mere vehicle through which Tarkovsky poses complex questions concerning our relationships to the self, love, life, and memories. Though a cosmic voyage, the movie is focused on inner exploration rather than outer; it’s a psychological experience that entrances the viewer through stunning cinematography, drawn-out shots, and a minimal soundtrack, inviting the viewer to stand alongside Kelvin on the space station to analyze their own life. There is such an alien and hypnotizing feel to Tarkovsky’s films that promote an almost hallucinogenic and transformative period of inner reflection. These movies crawl under my skin like bugs and embed themselves within me.

As a viewer, I tend to watch films that focus on the self and one’s attempts to make sense of their connection to the surrounding world, such as Solaris (1972), Synecdoche, New York (2008), and Sound of Metal (2019). While not influencing my work directly, I take a holistic approach to self evaluation, and recognize that the movies I enjoy help compose and explain who I am as a person. In my work, I often depict figures and faces as disconnected forms, each of which is insignificant on its own but when fit into the right place, forms a symbiotic composition. With this, I often begin with simple shapes until the structure and subject reveal themselves within my mind. It’s rare that I start out on something knowing where it will end up, and I would personally prefer not to know.

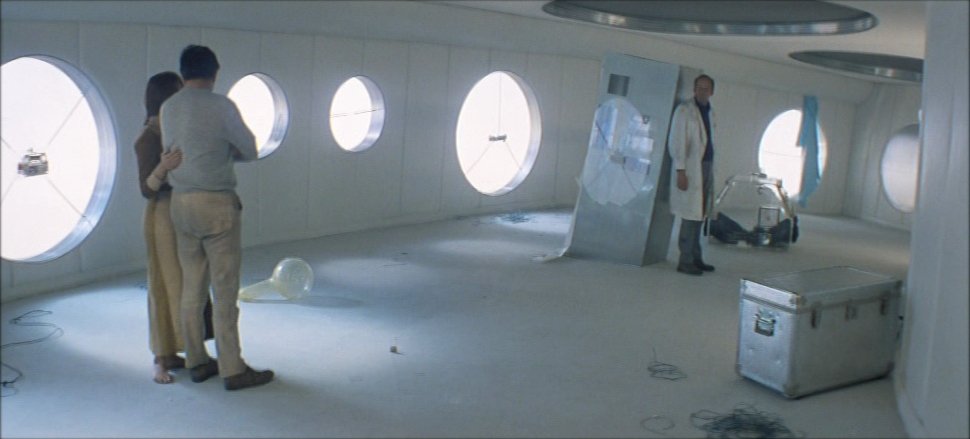

Solaris (1972) still from FILMGRAB

Solaris (1972) still from FILMGRAB

Boondoggle by John Swords, Ink and highlighter on paper, 2023

A huge thank you to the artists who participated! To learn more about our gallery members both as people and artists, visit our Artists tab, which can be found here.

Written by staff contributor John Swords.