“Into the Misty

Thierry Guillemin's landscapes, Leslie Kiefer's photocollages, & Deborah Addison Coburn's gouaches. Also: group shows, tactile or historical, and work by Pedro Ledesma III & Mak Dehejia

SEP 18, 2025

Thierry Guillemin, “Tuscan Staircase” (Studio Gallery)

PHOTOREALIST AND PASTORAL AT THE SAME TIME, Thierry Guillemin's paintings are precise yet atmospheric. The French-born local artist's latest Studio Gallery show, "Portrait of Ré as a Bird Photographer and other paintings" is titled after an atypical triptych. The selection, curated by Gaby Mizes, also includes one picture that's abstract but whose smudgy greens and blues suggest an out-of-focus landscape. The other five paintings observe heavily wooded parks, a light-dappled pond, or rustic roads and trails. All the scenes are enchanted by soft light and hazy air.

The title piece uses two paintings of birds to flank a woman (identified by Guillemin as "my muse, my love") who holds a telephoto-lensed camera. All three subjects are positioned dramatically on black backdrops, and the photographer is half-vanished into shadow. This is not the artist's usual approach. The other realist canvases feature near-photographic backgrounds and just a hint of human presence, usually offered by furniture or architectural details.

It's noteworthy that the artist continues his imagery onto the edges of his unframed paintings. This sense of continuation is significant to his pictures, in which everyday details center beguilingly long vistas. Often the compositions include passageways of a sort -- as tangible as a path or an outdoor staircase, or as ephemeral as a ribbon of low-lying mist. Guillemin's scenarios are tranquil and still, but they lead the eye on a journey.

THE NATURAL WORLD IS THE LITERAL SUBJECT of Leslie Kiefer's "Circe's Cavern: The Jewel in the Abyss," which hangs next to Guillemin's show. But the D.C. digital photographer's delicate images, which are composited in various ways, aren't simply observational. The pictures in this selection, also curated by Mizes, represent what the artist's statement calls "loss without the finality of death or closure."

Sometimes Kiefer locates an artifact that appears to illustrate the ability of Circe, the mythic Greek enchantress, to transform people into animals. A shed snakeskin, artfully draped, is a found metaphor for transmutation. The photographer often depicts flowers, but also a couple of shells -- only one contains a pearl -- and a pair of pumpkins, one vegetable and the other seemingly made of fabric. Kiefer occasionally interjects other manmade objects, notably a pink shoe from which a flower, also pink, seems to grow.

The wispy look of these pictures complements their pictorial themes. Multiple images are evocatively overlapped, soft hues suggest watercolor, and black and dark-green backdrops are layered and smeary. Everything appears fragile, yearning, and susceptible to change.

DEBORAH ADDISON COBURN IS KNOWN FOR WORKS, usually somber, that draw on her family's history. The local artist's "Divertimento," also at Studio and curated by Adah Rose Bitterbaum, has a similar origin but a very different vibe. These collage-paintings are bright and kinetic, full of figures in motion. Viewers will likely not be surprised to learn that the pictures were inspired by Coburn's own childhood drawings.

While the subjects are simple and the compositions naive, the use of color is more sophisticated. Experimenting with gouache for the first time, Coburn pits vivid colors against softer, more watery hues that flow and blend. Also more grownup, if in a playful way, are the transfigurative motifs of such pictures as "Swan Lake" and "Single Cat Ladies." In these Circe-like scenarios, women cavort with animals and sometimes become partly avian or feline. It's an intriguing parallel that Coburn's humans and animals mingle much as her colors meld.

Robert Johnson, “Potbelly Owl” (photo by Mark Jenkins)

THE FIRST CLUE THAT "ORDER AND CHAOS" IS AN UNUSUAL ART SHOW is the supply of blindfolds at the entrance. The U.S. debut of a Portuguese series, the pop-up exhibition is designed for visually impaired visitors -- and those who mask their eyes for a purely tactile experience. Most of the 12 participating artists, largely selected by local co-curator Elizabeth Casqueiro, are from the D.C. region.

Casqueiro has contributed two new pieces whose compositions resemble those of her collage-like, mostly representational paintings. But these artworks translate the paintings's style into three dimensions by adding such fingerable elements as pegboard. Other artists who often make sculptural work offer pieces in their usual modes, but these aren't meant just to be seen. Gallery goers can touch Susan Hostetler's ceramic birds, Kristina Penhoet's knotted-felt curtain, Robert Johnson's "ball" of orbiting plywood strips, and Wilfredo Valladares's rough-edged bowl filled with chunky, nut-like orbs.

Many pieces are constructed of found objects, which provide a range of intriguing textures. At the risk of betraying the spirit of the show, the assemblages are also appealing visually. Such fanciful creatures as Johnson's "Potbelly Owl" or Chinedu Felix Osuchukwu's "Chiquita" -- made largely of feathers or scrap metal, respectively -- are more than the sum of their motley parts. But those parts can also be examined one by one, feel by feel.

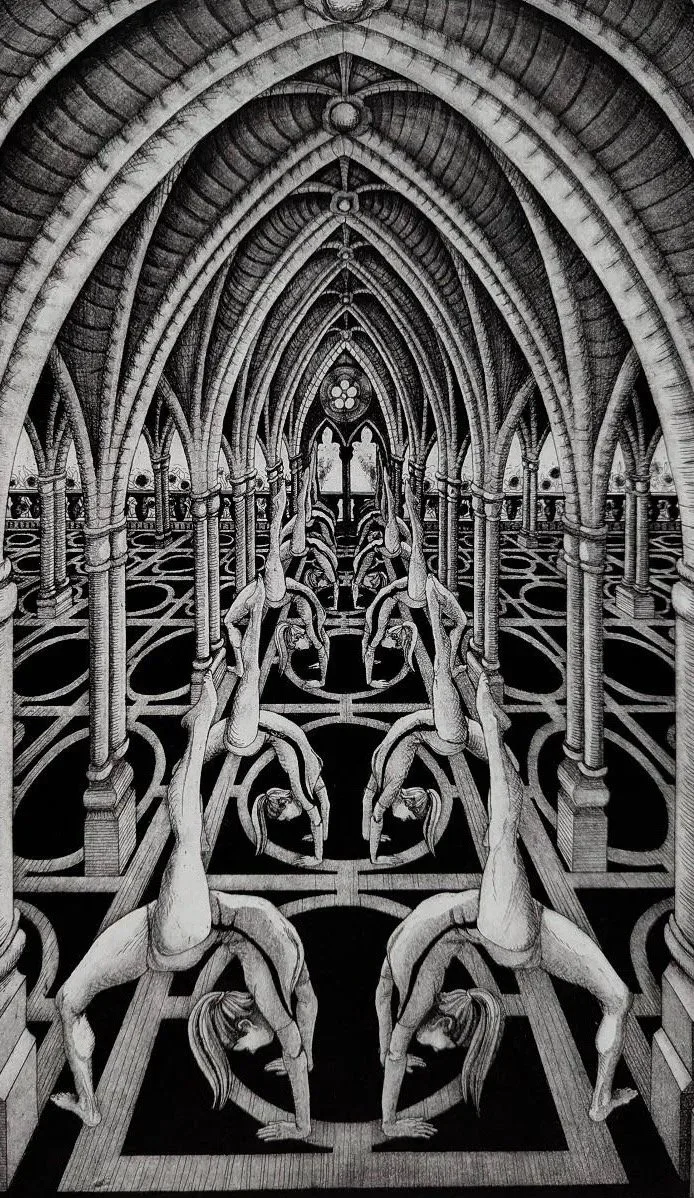

Deborah Schindler, “Vaulting” (Washington Printmakers Gallery)

FOUR DECADES OF A GALLERY'S LEGACY ARE CONDENSED into a few more than 40 prints and photographs in "Then & Now: Celebrating 40 Years of Washington Printmakers Gallery." The 24 participants, eight of them WPG founding members, are exhibiting two works each, one from "then" and one from "now." The route from one era to the other is not always straightforward.

Among the highlights are Deborah Schindler's elegant etching and aquatint, "Vaulting," in which two queues of exceptionally agile gymnasts project their legs skyward in emulation of the arched cathedral-like space in which they're lined up. The picture's sense of structure and perspective is echoed in a very different scene, Bob Burgess's "Sprayers," a photograph of agricultural workers in a field whose parallel furrows have a geometric exactness. In Kristine DeNinno's intriguing aquatint etching, the mostly orderly rows are partly slipped and blurred, perhaps to represent the effects of its title subject, "Fog."

Rosemary Cooley neatly contrasts a precise Renaissance-style architectural rendering with a looser rendering of a flower in her two-part intaglio print, "Individuation." Nina Muys's two monoprints both depict sunflowers, but the older picture is soft and subdued, while the newer one is harder-edged and, well, sunnier. Susan Pearcy's poignant "Sunflower Leaf #8" is sort of vegetative memento mori, a drypoint print finished with pastel that adds just the most desiccated shades of yellow and tan.

Perhaps it's a coincidence, but there's a wistfulness to many of these pieces that befits a retrospective show. Yet the pensiveness can be infused with drama, as in William Demaria's "Ghost River." This stark monoprint engraving depicts a stream with dark banks and a branch that casts a unifying shadow from one black shore to the other. The scene is set on a white field, as if to suggest that the moment is emerging from or receding from time. The vignette could be coming or going, then or now.

Pedro Ledesma III, “Mr. Julian Green, Jr.” (courtesy of the artist)

VENERABLE FIGURES ARE PORTRAYED WITH GREAT DIGNITY in "Our Rich (African) American History," photographer Pedro Ledesma III's show at the Arts Club of Washington. Many of the portraits were made in churches, and their subjects pose with suitable dignity and solemnity. Somberly, Ledesma has covered with black veils the pictures of two people who have since died.

Photographed in Petersburg, Va. in 2023, the pictures mostly depict older people whose formality is both a declaration of self-respect and a means of self-defense. If many of the subjects recall the besuited activists of the early-1960s civil rights movement, Ledesma's style evokes an even earlier time. Expertly lighted, the portraits suggest the Dutch Golden Age painters who highlighted faces amid lush black shadows. In Ledesma's photo of Julian Green, Jr., both the man's face and the large book in front of him are immaculately haloed.

The photographer did memorialize a few funkier figures, including a younger man who sits in a bar, wearing a pink cowboy hat. Central to Ledesma's project is the late Richard Stewart, who collected thousands of items for his one-man archive, the Black History Museum of Pocahontas Island. He's pictured surrounded by photos, artifacts, and hand-lettered signs. Ledesma's picture of Stewart is a superb example of environmental portraiture, but it's also an expression of affinity between two historians of the Black experience.

MARYLAND ARTIST MAK DEHEJIA USES WATERCOLOR TO CONVEY the liquidity of lakes, rivers, and misty air. So it's a bit surprising to learn that his late-in-life artistic career is rooted in his experience, as a child in rural India, of colorful sunsets caused by dust storms. Less perplexing is a boyhood attraction to "streams and ponds" that "provided relief from the hot sun," according to his statement about his Park View Gallery show, "Tranquil Vistas."

There's little sense of heat in Dehejia's small impressionist landscapes, but lots of light. Orange, pink, and areas of unpainted white convey the effects of sunlight, whether filtered through clouds or reflected on rippling surfaces. The places where sky meets water hint that each is boundless, and very nearly capable of flowing into each other. These serenely fluid locations seem to exist outside the influence of people, of which there is almost no evidence in the paintings.

Luminous color and satiny forms are what is immediately striking about Dehejia's work. Just as impressive, though, is the way the artist juxtaposes flat and modeled forms. He conveys trees, for example, with just a few green blotches. But he's also capable of layering multiple colors to conjure depth and distance. Dehejia's pictures appear as moist as his medium, but perhaps they do carry some memory of the vast skies that nature painted above decades ago.

Thierry Guillemin: Portrait of Ré as a Bird Photographer and other paintings

Leslie Kiefer: Circe's Cavern: The Jewel in the Abyss

Deborah Addison Coburn: Divertimento

Through Sept. 27 at Studio Gallery, 2108 R St. NW. studiogallerydc.com. 202-232-8734

Order and Chaos

Through Sept. 27 at Realces pop-up gallery, 3307 M St. NW. realces.pt/order-and-chaos. Open by appointment: ecasq@realces.pt

Then & Now: Celebrating 40 Years of Washington Printmakers Gallery

Through Sept. 28 at Washington Printmakers Gallery, 1675 Wisconsin Ave NW. washingtonprintmakers.com. 202-669-1497.

Pedro Ledesma III: Our Rich (African) American History

Through Sept. 26 at the Arts Club of Washington, 2017 I St. NW. artsclubofwashington.org. 202-331-7282.

Mak Dehejia: Tranquil Vistas

Through Sept. 28 at Park View Gallery, Glen Echo Park, 7300 MacArthur Blvd., Glen Echo. 301-634-2274.”

Written by Mark Jenkins in DisCerning Eye, thank you!