“Easy on the Eyes: The Best in Local Photography Exhibits for 2025

City Paper’s longtime photography critic rounds up his seven favorite shows of the year, from Jo Levine’s seamless presentation of overlapping layers to Colin Winterbottom’s mix of old-school black and white, sepia toning, and color UV pigment on aluminum.

LOUIS JACOBSON

DECEMBER 9TH, 2025

“Clam Digger,” Courtesy of Vincent Ricardel and gallery neptune & brown

In the quarter-century-plus that I’ve been a City Paper photography critic, my year-end list of the best photography exhibits in the D.C. area has usually included a couple of nods to larger museums. Not this year. Maybe it’s just coincidence, but in 2025, each of the seven exhibits on my list were held in spaces where it would be only a modest exaggeration to say you could reach your arms out and touch two opposing walls at once.

Since 2001, I have assembled a list of the top exhibits in the D.C. area on a (mostly) annual basis. This year, I’ve selected—and ranked—seven exhibits that merit a place on the list of best local photography exhibits of 2025. I also offer shout-outs to three visual arts exhibits beyond the bounds of photography.

This year’s list of best D.C.-area photography exhibits is dominated by such cozy confines as gallery neptune & brown, Alexandria’s Multiple Exposures Gallery, Studio Gallery, the Byrne Gallery’s temporary D.C. outpost, Photoworks, Foundry Gallery, and Georgetown University’s Lucille M. & Richard F. X. Spagnuolo Art Gallery.

Here’s the rundown:

Vincent Ricardel’s 15 images may have been largely observational photographs in urban and natural areas, but stylistically (and geographically) they were all over the map. Alternating between black and white and color, Ricardel channeled Karl Blossfeldt’s botanicals, Harry Callahan’s ultra-high contrast of snow and sand, Eugène Atget’s Parisian streetscapes, Andy Warhol’s matrices of muddily rendered faces, and Henri Cartier–Bresson’s “decisive moment”—in Ricardel’s case, an image featuring a girl, a cat, and more than a dozen pigeons, each in motion. Ricardel even hat-tipped Katsushika Hokusai’s famous wave with a dark moodiness, seemingly threatening a mostly submerged figure nearby. Ricardel’s work often involved partial or bent legs—one foot emerging from a building window, several belonging to ballerinas, one belonging to the girl with the pigeons, one from a cross-legged man partially obscured by a tree, one sticking out of the water in East Hampton, New York, and a pair belonging to schoolgirls on a sidewalk, captured as they’re walking out of the frame. For a photographer with such divergent styles and methods, this habit counted as the one unifying theme of his work.

“Legs with Glove,” courtesy of Vincent Ricardel and gallery neptune & brown

“Yucca Rocks No. 2” by Tom Sliter

Rarely has a photographer’s choice of using sepia toning instead of standard black and white made as much of a difference as it did with Tom Sliter in Chiseled by Time: Sculptures of the Mojave Desert, Sliter, a D.C.-area photographer, parked himself in California’s desolate Mojave Desert, capturing a mix of landscapes and close-ups of boulders and desert flora. In the desert’s overwhelmingly beige environment, Sliter’s sepia palette worked better than either color or black and white would have. His fine-grained digital images paid off the closer the viewer got to the photograph, revealing mottled, dimpled, and crevassed rock surfaces and the delicate spikes of yucca fronds. One image gainfully paired rough rock surfaces with an angular, starburst-shaped portrayal of the sun; other photographs portrayed smoothly weathered boulders as if they were fleshy skin pics. Sliter’s standout image was “Joshua Tree Boulders,” a sharply horizontal landscape that combined gently undulating layers of sky, mountains, boulders, and shrubbery and offered enough detail to somehow show every individual clod of earth.

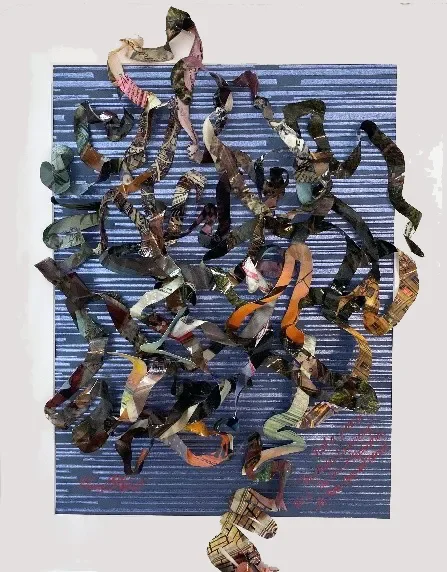

“Sky Lights #1” by Jo Levine on View at Studio Gallery

Jo Levine, whose past work at Studio Gallery and elsewhere has often beenimpressive, outdid herself in this four-person exhibit, documenting an array of locations in D.C. and elsewhere. What tied Levine’s works together was a seamless presentation of overlapping layers. In one photograph, Levine captured the crisp reflection of the Empire State Building off the smooth hood of a black car. In another, Levine documented a flurry of hanging light bulbs reflected in a window, cheekily suggesting a UFO invasion above an ordinary-looking street scene. In a third image, Levine presented an almost literal kaleidoscopic view of reflections on the mirrored exterior of a building. While Levine structured many of her photographs around the rigorous lines of modernist architecture, many of them included unexpected buckling, as if the lines were being shaped by some unseen magnetic force. Levine’s two finest images may have been her most abstract. One depicted the organic, gently undulating surface rivulets of water in pleasing shades of olive and gray. The second captured a view of the Kennedy Center’s REACH, bringing together a satisfying mix of straight and curved geometric lines, appealing shades of Hopperian blue and gray, and a dreamy, watercolor-like texture that came from gentle disturbances in reflected water.

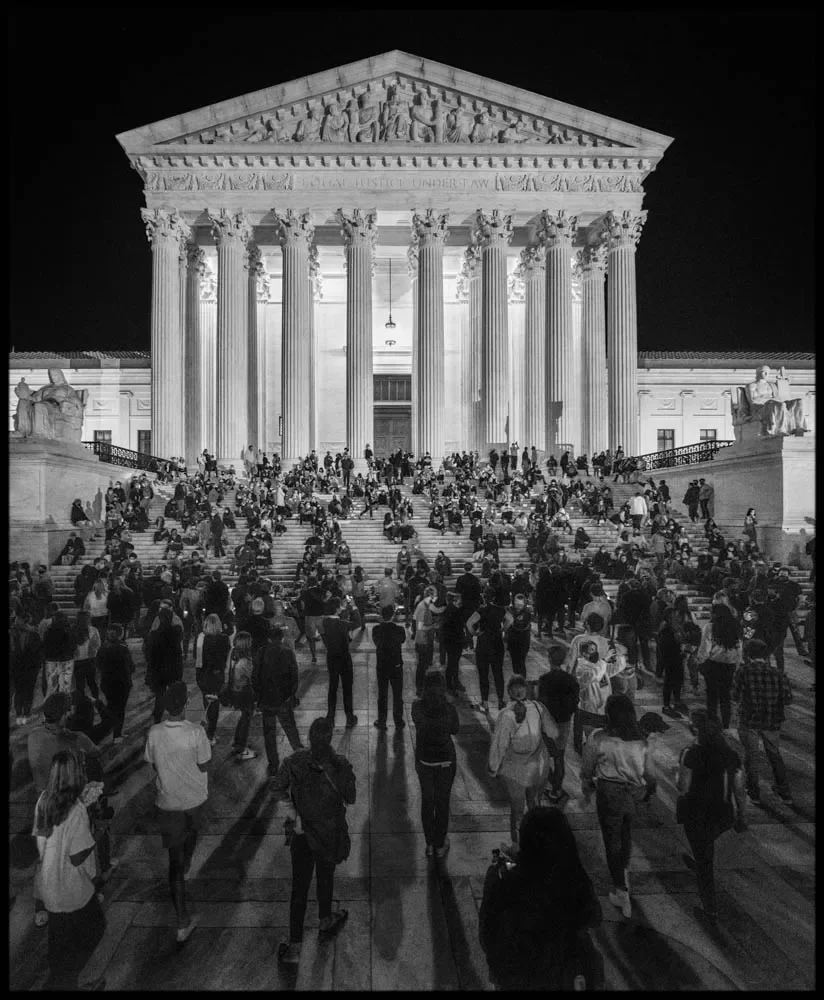

Credit: Colin Winterbottom

Iconic Washington was a two-person photography exhibit, but the standout was Colin Winterbottom. His works included several large-scale images from his ongoing series documenting Washington’s National Cathedral, notably his time-lapsed “Apse with Star Trails,” which smartly paired the solid stone of the cathedral’s facade with the fleeting, semicircular flickers of stars moving through the night, and his “Apse from Tower,” which featured a soaring cathedral spire shown off-kilter and amid murky lighting, as if it were an extrusion from an underwater shipwreck. Winterbottom’s works used a mix of old-school black and white, sepia toning, and color UV pigment on aluminum. He leveraged the last of these methods to perfection in an image in which the Lincoln Memorial was mostly obscured by a series of broad steps; the dreamy, wintry setting clashed fruitfully with the sharply minimalist aggregation of narrow, parallel stairs.

5. Timeless 2025: Handmade Photography in the Digital Age at Photoworks

Photoworks’ Handmade Photo Group exists to produce imagery from gloriously archaic techniques, and once a year, they mount their bounty. As usual, this year’s exhibit was satisfying. Mari Calai’s subject matter was straightforward—a carpet of spiky leaves, a high-contrast portrayal of a V-shaped valley and sky, and a promontory topped by a bent tree—but her platinum-palladium process on vellum, highlighted with touches of gold leaf, elevated her scenes into something winningly out of our era. David Frey, one of several artists who worked with the cyanotype (blueprint) method, toned his works with ingredients ranging from avocado or black tea; his method worked best with a subtle, purple-hued botanical image and an orange-toned photograph of a lotus pod. Christopher Gumm used the gum bichromate process to produce a dreamy, pictorialist rendering of water lazily traversing littoral greenery. Two artists went a step further by experimenting not only with the photographic process but also with the surface they were printing on. Zoe Kosmidou turned paper bags into canvases for printing, then decorated her works with mixed media. Even more inventive was Mac Cosgrove-Davies, who made wet-plate collodion images of trees and people that he applied to crushed beer cans. The images themselves were worthwhile, but with a substrate as creative as that, it almost didn’t matter what he was photographing.

6. Aftertime at Foundry Gallery

Gordana Geršković, “THE CONVERSATION or DOG meets FISH,” Photography, 11×14

Shaw’s Foundry Gallery mounted another exhibit by photographerGordana Geršković in 2025, and while her style hasn’t changed a whit since her first in 2019, she’s managed to keep her photographs compelling and fresh. Geršković, whose works were paired in the gallery for the second time with paintings by Deb Furey, created her photographs by walking around in search of city facades with accidentally compelling designs caused by weathering and decay. Some of the resulting images were unfussy, such as the paired images that featured Mark Rothko-style color fields in shades of blueberry, raspberry, and cherry. More often, Geršković found her target in complexity: white drips on red that approximated the shape of a tree standing on a hillock; an image that looked like a cross section of beige-and-ocher sedimentary layers; a “storm” made of blue marks seemingly in wavelike motion; a riot of splotches that suggested a Jackson Pollock painting; and a pink and dark blue-green melange that called to mind a late Willem de Kooning.

In most photographic exhibits, the stars are the photographs, or perhaps the photographer. In & Loving, however, the focus was—refreshingly—the curators. Six Georgetown University students—Ella Boasberg, Madeleine Callender, Caroline McCann, Amelia Myre,Khaki Sawyer,and Tess Whitman—assembled a 13-image exhibit from a 4,000-photograph archive at the university. The theme was a “sense of love,” and the curators nailed it—not just in their choices of images (a Larry Fink photograph of a beaming high school graduate, Ken Heyman’s photograph of an ecstatic crowd at a 1968 Beatles concert, Erika Stone’s photograph of two older women chatting on a park bench, surrounded by pigeons in flight), but also in their smart, yet brief, captions. Visitors learned how the smiling woman in a Donna Ferrato photograph was at peace because she had escaped domestic abuse; they also came to understand how Earl Hines, shown exuberantly mid-performance during a 1958 concert in San Francisco, shaped the practice of jazz piano during his career. The exhibit included a contact sheet of surprisingly sprightly, medium-format black-and-white photographs from a 1960s basketball game between Georgetown and the University of Miami, marked up with an orange grease pencil. This work may not have fit the theme of “loving,” but in this company, it was charming nonetheless.

Courtesy of Spagnuolo Gallery

Three notable 2025 exhibits in painting:

Wayson R. Jones with some of his art at Hemphill Artworks. Credit: Louis Jacobson

Wayson R. Jones at HEMPHILL Artworks

Wayson R. Jones’ works on display at HEMPHILL were inventive both in their colors and their method. He laid down pumice gel, mostly of the “extra coarse” variety, then used repurposed tools to shape the drying gel into patterns that tiptoed between organic and orderly. After letting those sit for a few weeks, he used Flashe, a vinyl-based paint, to turn his surfaces into bold, candy-colored works that wrapped around the frame and up into three dimensions. The result was often the texture of volcanic rock. One series of smaller works suggested wavelets of sea-foam coming ashore on a beach, except that the “beach,” if that’s what it was, was ocean-like blue, and the wavelets ranged from purple to orange. A trio of larger works featured roughly parallel, but wriggly, crests that were painted, respectively, in Wayne Thiebaud yellow, Frango mint blue green, and two shades of red. Other works were made with a rake-like tool to create semicircular forms that suggest 1970s-style mod artworks. One piece, “Hot Stepper,” harnessed the Flamin’ Hot Cheetos aesthetic, with raised, bumpy portions painted in spicy red and the anarchic voids in a slightly greenish yellow. The gallery paired Jones’ canvases with those of Leon Berkowitz (1911-1987), a key member of the abstract-oriented Washington Color School. In the works on view, Berkowitz turned orange imperceptibly into blue, and red slowly into green.

Radiant Detritus at Addison/Ripley

Trevor Young’s latest show at Addison/Ripley echoed many of his previous exhibits, including such recurring themes as ugly-beautiful power lines, highway flyovers, empty billboards, and artificially lit industrial nocturnes. But he also added some twists. An unusually large number of the four dozen paintings on display were rendered in a moody shade of blue; occasionally, Young toyed with an odd black shadow encroaching on the main portion of his landscape. One monumental, starkly horizontal work depicted a sprawling gas field limned with rusty amber lighting that felt like something out of Edward Burtynsky’s catalog; another painting featured an unsettling, unfinished, multistory metal structure crisscrossed by stairs and illuminated by multiple, diaphanous showers of light. Young’s most satisfying work may have been “Tolls,” which looked out over four parallel barriers (highways, maybe?) plunged into dark blue purple yet sitting beneath a creamy white sky—a mutually reinforcing mix of color and geometry in a tiny 12-by-12-inch package.

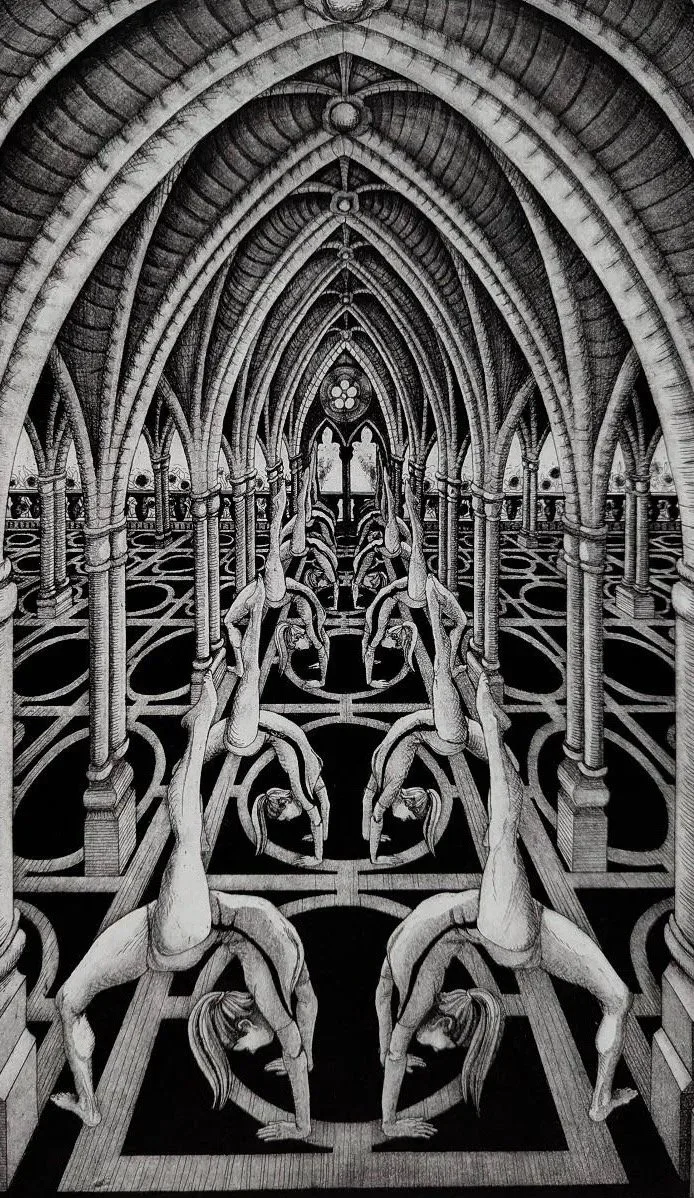

Amy Schissel at HEMPHILL Artworks

Amy Schissel’s exhibit included both monumental, mostly monochromatic canvases, some just shy of 19 feet wide and some as tall as 8 feet, as well as smaller, brightly colored abstractions. The process of making the largest works was laborious, sometimes taking as long as 300 hours; they involved multiple coats of paint, often massaged into organic highlights, followed by painstakingly detailed patterns drawn in ink—radiating straight lines; geometrical shapes; loops and whorls; and the occasional spirograph form. In their entirety, the large canvases suggested a frenzied, wide-screen digital universe, with touches of steampunk, topographical maps, neural networks, and surreal dreamscapes. Schissel’s intensely colored abstractions were smaller and not as stunning in sweep, but their contents were noteworthy—forms that were alternately angular and landscape-like, in bright, LeRoy Nieman-esque shades of blue, green, pink, and beige. Schissel explained that she creates the color canvases in order to get those colors out of her system as she creates the all-enveloping grayscapes. One can see why.”

Written by Louis Jacobson in the Washington City Paper, thank you!